Allegory and strange caricatures

Carracci’s brothers

A group of portrait Annibale, Ludovico and Agostino Carracci by the Bolognese School. 17th century. Members of the Caracci family are considered the founders of caricature. Image by Wikipedia

The next step from the detached aesthetic exploration of Leonardo was taken by the Caracci Family: Agostino (1557-1602), his brother Annibale (1560-1609), and his cousin Ludovico (1555-1619)[Fig. 1], considered the inventors of caricature. By reducing a man’s likeness to a few insulting lines, these artists were able to exert a magical influence over the person they portrayed. In caricature of the kind perfected by the Caracci we encounter a new twist on the idea of virtuosity, itself so typical of both Mannerism and Baroque. In the Caracci and their successors it was the power to conjure up images in a moment, with only few lines or strokes of the brush. The merit of these conjuring tricks lies in the artist’s ability to seize the essentials of the subject matter. We find this ability not only in the work of Caracci family, but even more so in other European artists of the early Italian school such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), Giovanni Francesco Barbieri known as Il Guercino (1591-1666), Pier Francesco Mola (1612-1666), Pier Leone Ghezzi (1674-1755), and Anton Maria Zanetti (1679-1767) who recognized in the facial expression the essential elements of caricature.

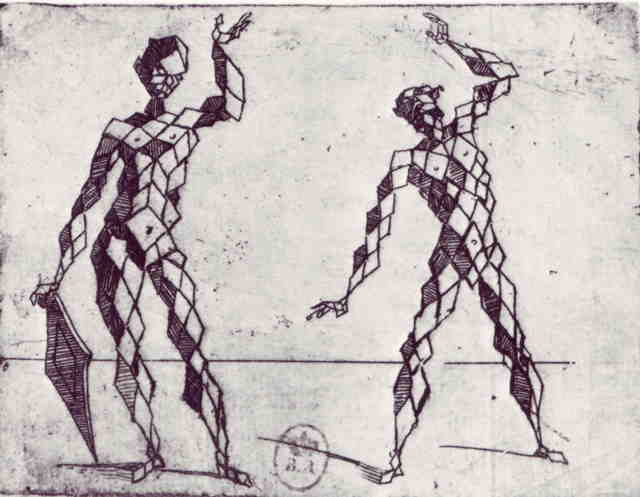

Acrobatic figures

“Acrobatic figures”, in “Bizzarre di varie figure”, circa 1624. Giovanni Battista Bracelli’s drawing do not have a satiric intention but demonstrate how caricaturists could represent people and gestures abstractly and rendered them by a ready-made graphic formula. Image by Wikipedia

The widespread fashion in the 16th and 17th century for treating the human figure in an abstract or schematic way is typified in a series of prints by Giovanni Battista Bracelli (1616-1650)[Fig. 2]. A different approach was that of Arcimboldo Design. This cannot be described as caricature since there is no evident satiric intention, but it demonstrates how artists could look at a person and their gestures abstractly so that any individual or event could be rendered by a ready made graphic formula. Bracelli is considered a precursor of Surrealist art from the Italian Renaissance. It was also a favorite of the Romanian artist Tristan Tzara (1896-1963). In Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s (1537-1593) paintings his surrealist fantasy is more elaborate, his portraits are formed of a conglomeration of different objects [Fig. 3].

“Reversible head with fruit basket”, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, circa 1590. The Mannerists tended to show a close relationship between human and nature. An example is Arcimboldo who created hidden faces in arrangements of flowers, vegetables, fruit, animals, books and different things on the canvas in such a way that the whole collection of objects formed a portrait. Arcimboldo’s heads are surrealistic and considered a particular approach to Physiognomy. Image by Wikipedia

Arcimboldo’s fantasy

This is a typically Mannerist conceit, the various features actually become what they most resemble. The long established medieval fashion for monstrosities, which can be seen in prints depicting anatomical curiosities of all kinds, is obviously related to Arcimboldo’s technique. Arcimboldo’s famous heads were influenced by the grotesque heads of Leonardo and considered a different approach to Physiognomy in relationship with natural elements.

Arcimboldesque figure

“Habit d’apoticaire”, Nicolas IV de Larmessin, 1695. An Arcimboldesque figure made up of components relating to apothecary, surrounded by medicinal plants. Image by Wellcome Library no. 16386i

Callot’s cripples

“Grotesque figure”, Jacques Callot, 1622. Grotesque figure (poliomyelitis?) of a man with a peg leg and leaning on a crutch. Callot’s cripples, freaks, and beggars are caricatured in the highest sense of the word, though their humor is stringent and pessimistic. Image by National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, USA

After Arcimbold’s time, the technique of constructing a human creature out inanimate objects remained popular with designers of fantastic prints. The main artist of this genre was the Frenchman Nicolas IV de Larmessin (1684-1753) who published figures of tradesmen constructed of objects connected with their own profession. The same style can be seen in the British Charles Williams (1797-1830), whose witty caricatures are composed of professional tools and related objects [Fig. 4]. In the lighthearted 19th century variation, Williams revived an old form invented by Arcimboldo. More human, and therefore more essentially humorous, are the figures of dwarfs by Jacques Callot (1592-1635) [Fig. 5] and Stefano della Bella (1610-1664). These paintings represent not only the dwarfs and pygmies as were done in classical antiquity but the passion for deformity which prevailed in the Northern Europe with the German Daniel Hopfer (circa 1470-1536), the Dutch Pieter van der Heyden (circa 1530-after 1572), Hieronymus Bosch (circa 1450-1516) who filled his painting with bizarre creatures [Fig. 6], and later the Flemish Pieter Brueghel the Elder (circa 1525-1569) manipulated Boschian forms to transform men into symbolic objects.

Regardless of historical context artists have traditionally turned to a standard repertoire of compositional devices and visual formulas to help make their humorous points. Among these are the exaggeration and agglomeration of faces and bodies, the depiction of people as animals and objects, and the display of caricatural figures in different ways. The absurd contrast, deformity, and nonsense situations create a primal appeal that allows us to recognize the humour of a caricature even if we are unfamiliar with the specific subject matter or situation represented. Caricaturists from all periods play similar games with our minds.

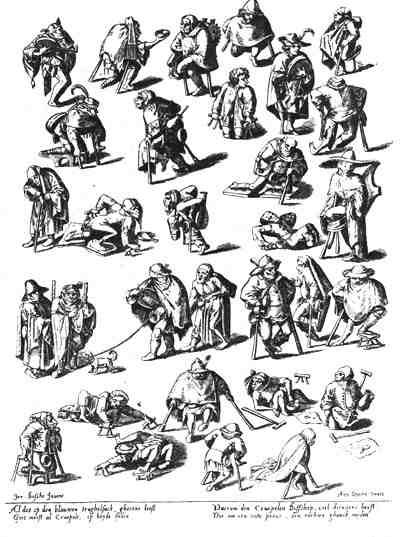

Procession of the Cripple

“Procession of the Cripple”, Hieronymus Bosch, circa 1500. Clinical features of 31 disabled cases. In the 16th century in the Netherlands, many cities held a two day procession, called “ommegang” which took place on the Monday and Tuesday after Epiphany to collect money for lepers. Bosch’s drawing portrays this procession. Dequeker (2001) suggests that Bosch’s illustration shows congenital developmental disorder, ergotism in three cases, post-traumatic amputation, neurofibromatosis, poliomyelitis, the sequelae of generalized atherosclerosis, amputation of the lower leg, spastic hemiplegia, suspects of simulating disability, one of whom is an alcoholic with possible polyneuropatis.

Dequeker J, Fabry G, Vanopdenbosch L. Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516): Paleopathology of the Medieval Disabled and its relation to the bone and joint decade 2000-2010 . IMAJ 3: 864-871, 2001. Image by Wellcome Library

References

- McPhee C C, Orenstein N M. Infinite Jest. Caricature and satire from Leonardo to Levine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2011

- Catalogue. Rabisch. Il grottesco nell’arte del cinquecento. Milano, Skira, 1998

- Ferino-Pagden S. Arcimboldo: artista milanese tra Leonardo e Caravaggio. Milano, Skira, 2011