“Caricatural” journals

In Europe, the spread of journals which focused on the art of caricature was associated with the development of printing techniques. The earliest offerings were the French journals La Caricature (1830) and Le Charivari (1832) [Fig. 1]. These contained wood engravings which were incorporated with by letterpress, and, of far great importance, lithographs. In 1869, the innovation of chromolithography paved the way for the success of the British magazine Vanity Fair. Another source of succes for newspaper cartoons was the rise of elementary education in Britain, Germany, France and elsewhere which created a new readership who desired pictures be included with text. Following the success of La Caricature many satirical papers were launched. Most were short lived, but Punch (1841), Kladderadatsch and Fischietto (1848), Le Journal Amusant (1856), Vanity Fair (1868), Le Chat Noir (1882) and the Germany weekly journal Simplicissimus (1896) thrived.

French magazines

Charles Philipon (1800-1861) is considered the founder of caricatural journalism in Europe with his satirical weekly La Caricature in 1830. This journal immediately overstepped the mark and was seen as undermining Authority. However, La Caricature ceased publication soon after for financial reasons. Philipon went on to publish the metamorphosis in full in his daily paper Le Charivari (1832). Caricatures had to be generalized, directed not against individual power but against traditional social targets to avoid political difficulties. In this art the French were ascendant. Philipon and his colleagues were imitated and emulated in other countries, Britain in particular. Philipon had many collaborators such as: Paul Gavarni (1804-1866), Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville (1803-1847), Achille Jacques-Jean-Marie Devéria (1800-1857), Denis Auguste Marie Raffet (1804-1860), André Gill (1840-1885) and the most important French caricaturist Honoré Daumier (1808-1879).

Daumier interpreted the social change in France observing the transformation of the medical profession and practice with many caricatures published in caricatural journals La Caricature and Le Charivari . Some of Daumie’s pictures were also collected in François Fabre’s book : Bureau de la Némésis médicale (1840). One of the main medical topics of Daumier and his friends was Phrenology and the emerging Neuroscience. The caricatures on these themes made their readers aware of the need for a scientific basis of these new ideas.

Le Charivari

Le Charivari was the most important caricatural magazine in France and in Europe founded in 1832 by Charles Philipon (1800-1861) and ceased its publications in 1893. This figure depicts the First Minister Loiuse-Philippe Duke of Orlėans (1773-1850) as a pear, in French poire means also fool (27 February 1834). Image by French Wikipedia

English magazines

Punch

Punch or London Charivari was the first and diffuse English caricature magazine founded in 1841 and ceased its publication in 1992. The picture is the front cover of the first volume depicts Punch hanging a caricatured Devil. Images by English Wikipedia

Punch, or the “London Charivari” was an English weekly magazine of humour and satire established in 1841 by Henry Mayhew (1812-1887) and engraver Ebenezer Landells (1808-1860). Historically, it was most influential in the 1840s and 50s, when it helped to coin the term “cartoon” in its modern sense as a humorous illustration. It became a British institution, but after the 1940s, when its circulation peaked, it went into a long decline, finally closing in 1992. It was revived in 1996, but closed again in 2002 [Fig. 2].

Vanity Fair

Vanity Fair was a English weekly magazine founded in 1848 and ceased its publication in 1914. The pictures is a front cover appeared on 1st September 1896. Images by English Wikipedia

Although Punch generally saw itself as a comic journal of mainly political and social content, analysis of the periodical’s first 30 years suggest that over 10% of all articles contained a scientific references of some kind or another. The first 30 years of Punch coincided with one of the most dramatic periods in the 19th-century science. Themes addressed included the sensation created by theories concerning biological evolution, the rise of government medical inspectors, and the training of women doctors. Punch also documented the development of “alternative” scientific practices, including mesmerism, homeopathy and spiritualism.

Vanity Fair was another satirical English weekly magazine which appeared from 1868 to 1914 [Fig. 3]. It offered its readers articles on fashion, current events, reviews of the theater, new books, reports on social events (and the latest scandals), and other trivia. Today, the old Vanity Fair is best remembered for its caricature prints. Vanity Fair was founded by Thomas Gibson Bowles (1842- 1922) to display the vanities of the week, typically a well known contemporary personality. Colored caricatures were added to the magazine after the first several issues in order to promote sales. Over 2000 of these caricatures were printed, of which 53 were of physicians. All of the medical caricatures were of British notables except the German Rudolph Vircohw (1821-1902) [Fig. 4], the French Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) and the American Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894). One surprising omission was Joseph Lister (1827-1912) the pioneer of antiseptic surgery. There were at least two well known artists that contributed caricatures to Vanity Fair. The first was the Italian Carlo Pellegrini (1839-1899) whose used the pseudonym “Ape”, followed by Leslie (later Sir Leslie) Ward (1851-1922) known as “Spy”.

“Cellular pathology” by Spy

Caricature of Karl Ludwig Rudolph Virchow (1851-1902), Vanity Flair, 1893.

In 1851, Virchow was the first to provide a detailed description of microscopic spaces between the outer and inner/middle lamina of the brain vessels later called Virchow-Robin spaces. Virchow was a German doctor, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist and politician. He is considered the “father of modern pathology” for his research using microscope. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, USA

German magazines

Kladderadatsch

Kladderadatsch was the first important Germany caricatural magazines founded in 1848 in Berlin and ceased its publication in 1944. This pictures is the front cover appeared on 9th July 1848. Image by English Wikipedia

The diffusion of German caricature in the press was to come many years later. The first important journal was Kladderadatsch (onomatopoeic for “Crash”) that first appeared on 7th May, 1848 in Berlin published by Albert Hofmann (1818-1880) and David Kalisch (1820-1872) [Fig. 5]. The journal ceased publication in 1944. The first artist for the journal was Wilhelm Scholz (1824-1893), He worked for the journal for 40 years. In 1884, Gustav Brandt (1861-1919) became one of the main illustrators alongside Wilhelm Scholz.

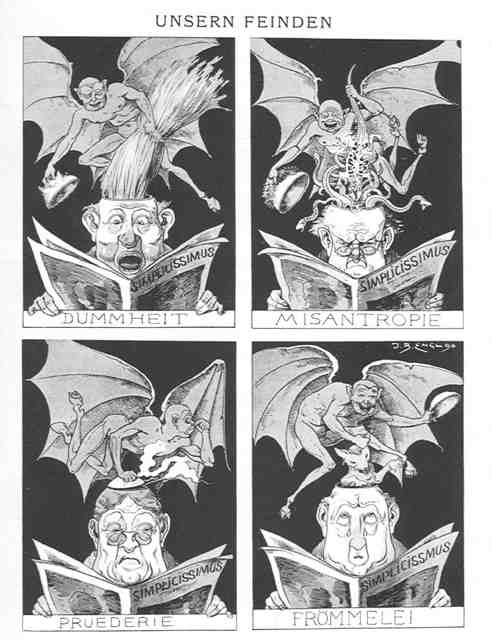

Simplicissimus

Simplicissimus founded in Munich in 1896 until 1967. This caricature by Josef Benedikt Engl (1867-1907) appeared Simplicissimus in 1896. The title is Our enemies: Asininity, Misanthropy, Coyness and Tartufism. Image by English Wikipedia

The most important German satirical journal was Simplicissimus a weekly magazine started by Albert Langen (1869-1909) in April 1896 and published in Munich until 1967, with an interruption from 1944-1954 [Fig. 6]. It took its name from the protagonist of Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen’s (1621-1676) novel Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch (Simplicius Simplicissimus) (1668). Simplicissimus published the work of writers such as Thomas Mann (1875-1955) and Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Illustrators and caricaturistis were: Rudolf Wilke (1873-1908), Thomas Theodor Heine (1867-1948), the Norvegian Olaf Gulbransson (1873-1958), George Grosz (1893-1959), Bruno Paul (1874-1968) and many others artists.

The journal adopted a new stylistic approach characterized by a concise, often abbreviated use of line, which echoes Neo-classicism. The typically powerful and muscular images were most notable in the journal Simplicissimus . In particular, Gulbransson reduced his caricature at the bare essentials: the bulk of the body, the line of mouth and eyebrow, the blank pince-nez, the single hair trained across the bald patch. This essential style was a characteristic of other Simplicissimus’ artists who depicted the decay in Society. Grosz produced explicit caricatures of German life, attacking the brutality and hypocrisy of Society of the 20th century, especially focusing on the bureaucracy of the Health System and Medicine. Simplicissimus described the evolution of Positivism and its ambiguities with another approach towards mental disorders: the emerging theories of psychoanalysis by Austrian Neurologist Sigismund Schlomo Freud (1856-1939).

Italian magazines

No fewer than four satirical magazines were founded in Italy in 1848. In order of appearance they were Il Don Pirlone (Rome), L’Arlecchino (Naples), Lo Spirito Folletto (Milan), and Il Fischietto (Turin). Of these Il Fischietto was the most politically challenging because its represented the future of the Union of Italy (1861) with its contradictions and hope in different fields including healthcare and the emerging medical specialists with neuroscience of which Camillo Golgi was the most important neuroscientist.

References

- Adhémar J. Les gens de Médecine dans l’œuvre de Daumier. Paris, Editions Vilo, 1966

- Anonimous. The first cartoon. History Today 55: 58-9, 2005

- Gould A. Masters of caricature from Hogarth and Gillray to Scarfe and Levine. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1981

- Holländer E. Die Karikatur und satire in der Medizin. Zweite Auflage. Verlag von Ferdinand Enke in Stuttgart, 1921

- Lucie-Smith E. The art of caricature. London, Orbis Publishing, 1981

- Key JD, Mann RJ. Caricatures in Vanity Fair. Medical Heritage. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders, pg 75-78; 1985

- Noakes R. Science in mid-Victorian Punch. Endeavour 26:92-96; 2002

- Mörgeli C. Das Bild des Arztes in der Karikatur am “Fin de siècle”. Schweiz. Rundschau Med 75: 1416-9, 1986

- Pappas DG. Targeted caricatures. The Laryngoscope 119: 1932-1936, 2009

- Sykes AH. The Doctors in Vanity Fair. Kendal, UK, Titus Wilson & Sun, 1995

- Thérenty M-E. L’esprit de la petite presse satirique: épigramme et caricature. Revue de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France 19: 15–20, 2005