Introduction

Caricatures and satirical cartoons have a long history of use in art and neuroscience. A caricature is a pictorial representation which by means of distortion creates a comic or satirical effect. The word caricature comes from the Italian caricare, which means to overload or to exaggerate, while the concept of ridicule only became linked to caricature in the Renaissance. By considering such graphic representations of individuals, institutions and innovations one can illustrate the main steps in the historical development of the neurosciences. European examples can be found in the sculpture, painting and graphic prints dating from Ancient Greece and Rome, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and succeeding centuries to the present. The humorous use of distortion has been adopted throughout many forms of artistic representation but its use to identify particular characteristics with specific individuals was only established by the late Renaissance.

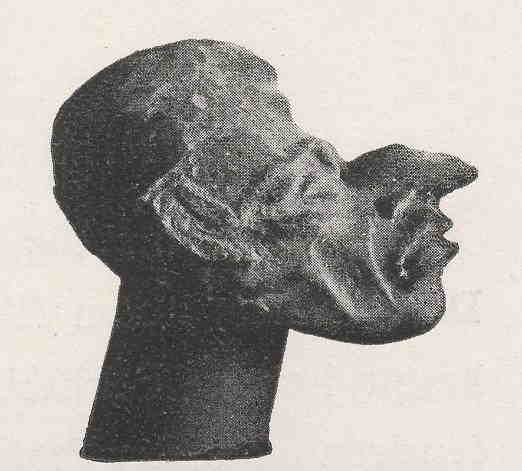

Grotesque Hellenistic head

Images by ‘Die Karikatur und Satire in der Medizin’ (Caricature and Satire in Medicine), Verlag Von Ferdinand Enke in Stuttgart, Zweite Auflage, 1921, by the German art historian and physician Eugen Hollander (1867-1932) (private collection).

Realistic representations of neurological conditions such as peripheral facial palsy are found on ancient Greek and Roman statuettes and vessel in depictions of scenes from life and literature [Fig. 1]. During the Middle Ages, art was more abstract and symbolic rather representational. Unnatural representations are found in the Grotesque reliefs and sculptures of medieval cathedrals, and in the “drolleries” that decorated the margins of Gothic prayer books. Neurological disorders interpreted from a religious or mystic point of view were used to enforce moral lessons, to portray sinners and the Dance of Death.

From the 1400s onwards, figurative representations in European painting and sculpture were underpinned by a deeper scientific understanding of both anatomy and perspective. Distortion became the distinguishing mark of caricature. The use of caricature for the purpose of ridicule developed the socio-political context marked by the breakdown of authoritarian social structures in medieval society and the subsequent emergence of the individual as a free agent. The Renaissance was, for all its progress, a period of inconsistency in the status of medicine. Caricatures often depict the doctor as a fool, but more scientifically and aesthetically based approaches to portraying neurological and mental states was also carried out by those high Italian artists such as Leonardo and Michelangelo.

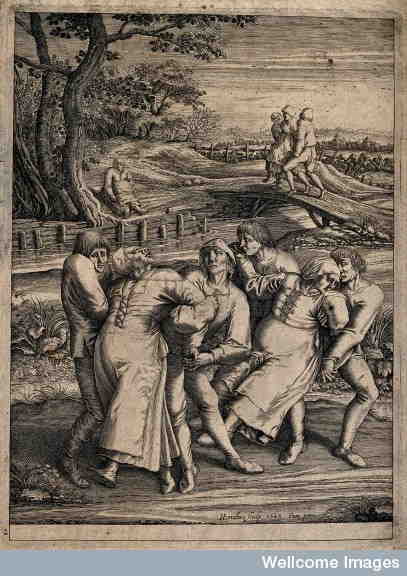

Brueghel’s neurology

Three epileptic women each supported by two men or dancing plague, choreomania, St John's Dance (historically St. Vitus' Dance). An engraving by Hendrick Hondius (1642) after a drawing by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1564). Image by Wellcome, London (UK)

During the 16th century, allegories became a favourite means of expression in the Arts. The Northern European illustrators as Pieter Breughel painted allegories filled with representations of life in the folklore tradition [Fig. 2]. This approach rejected the Renaissance aesthetic ideal of the classical body. These canvases were filled with depictions of people with medical disabilities. Medical treatments such as cranial operations and cautery, used as a cure of epilepsy, were also represented.

In the 17th and 18th centuries in France and in England caricaturists included representations of medical practices in their satires of the degradations of society. Physicians were portrayed as an oligarchy with control over the “lower orders” of practitioners. The medical feuds, jealousies and disputes that raged in the press and the law courts were also recorded by caricatures. The charged emotional atmosphere was represented by facial distortion for comic effect (the basis for the art of “Grimaciers”). This focus on the representation of facial expression was followed by the more systematic consideration of physiognomics, the developing understanding of the anatomy of expression which was later linked to phrenological concepts of the mental faculties.

In the 19th century, the new clinical-pathological exploration of the nervous system saw the employment of visual art incorporated into medical practice. One example is Jean-Martin Charcot who recorded essential features of neurological diseases in sketches and caricatures.

References

- Bergson H. An essay on the meaning of the comic. London, The Mcmillan Company, 1921

- Bozal V. El siglo de los caricaturistas. Historia del Arte. 29. Madrid, Cambio 16; 2001

- Caroli F. Storia della Fisiognomica. Milano, Leonardo Arte; 1998

- Kris E, Gombrich E. The principles of caricatures. Br J Med Psychol 16: 319–342; 1938

- Lorusso L. Neurological caricatures since the 15th century. J Hist Neurosci 17: 314-34; 2008

- Mitchell A. Greek vase-painting and the origins of visual humour. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press; 2009

- Wechsler J. A human comedy. Physiognomy and caricature in 19th century Paris, The University of Chicago Press; 1982

- Zigrosser C Medicine and the artist. New York, Dover Publications Inc; 1970