English caricaturists in the 18th-19th century

The great names of the 18th and early 19th century in England caricature were those of William Hogarth (1697-1764), James Gillray (1757-1815), Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) and the Cruikshanks, the father Isaac (1756-1811), and his sons Isaac Robert (1789-1856) and George (1792-1878).

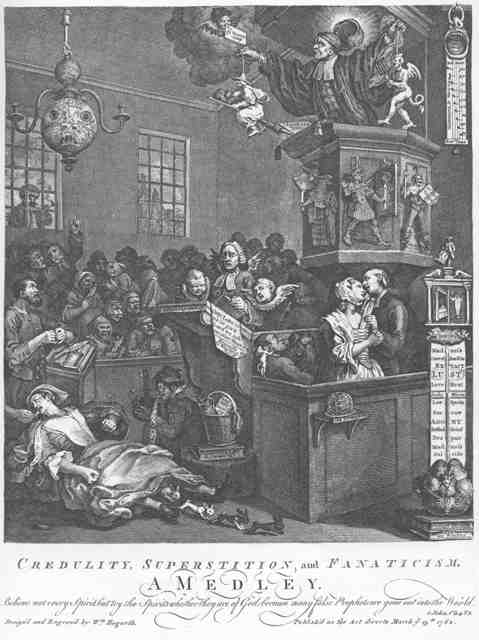

Hogarth is regarded as the founder of the English form for satirical art. He was described as graphic satirist and moralist. Hogarth’s comedy was based on observations of character, and the satirical content was based on elaborate and complex allegories [Fig. 1]. He despised the Italian caricatura as trivia distracting from the ideals of art. Hogarth’s pictures illustrate the position of influence that quack held in society. Hogarth highlighted the contemporary practice in which success in the practice of medicine did not always depend on qualifications, but often on patronage and, in the case of the quacks, advertising. Jealousies and enmity existed among the strata of the medical profession, physicians, surgeons, apothecaries and quacks. Hogarth depicted the battle among different levels in practicing medicine in England (physicians, surgeons, apothecaries and quacks).

Hogarth’s brain thermomether

Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, A Medley.

"Believe not every spirit, but try the spirits whether they are of God: because many false prophets are gone out into the world."

Caricature by William Hogarth, April, 1762

Hogarth’s targets in this print are the Methodists and the preaching of hell and damnation. An outlandish church congregation; symbolising the multiplicity of human folly. The preacher is the Methodist George Whitfield (1714-1770) who wears a harlequin’s costume under his cassock and a Jesuit’s tonsure under his wig; and the “ brain thermomether” (in the lower right corner) gives the temperature of his congregation which can rise to convulsion (the woman on the left of image) and madness (the behind crowed people). This “brain thermomether” is likely adapted from that of the architect Christopher Wren’s (1632-1723) illustration in Thomas Willis’ (1621-1675) The Anatomy of the Brain and Nerve (1631). Hogarth’s print is about humbug and chicanery and combines allegory with realism. Image by Wikipedia

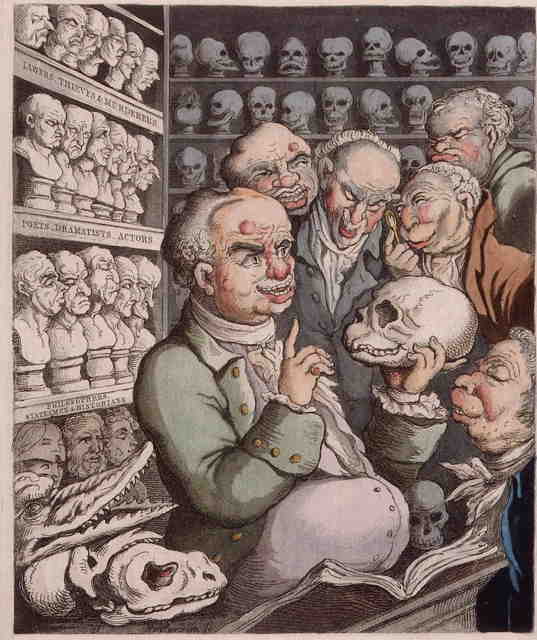

Thomas Rowlandson, Hogarth’s successor in British caricature produced more than 1300 satirical prints published both as single sheets and as book illustrations, about fifty are of considerable medical interest [Fig. 2]. Rowlandson’s interest in medical themes began with his studies at the Academy of Art which brought him in contact with the Scottish anatomist and physician William Hunter (1718-1783), brother of the famous surgeon John Hunter (1728-1793). Rowlandson’s interest was further developed by his friendship with physician John Wolcot (1738-1819). Wolcot had obtained his medical degree but abandoned medicine for literature and especially in writing satires. Rowlandson’s convivial life and passion for gambling lived a life in debt.

Thomas Rowlandson’s Gall

Caricature by Thomas Rowlandson, 1808

Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) leading a discussion on phrenology with five colleagues, among his extensive collection of skulls and model heads. The three shelves of model heads behind Gall are labeled: "Lawers, thieves & murderers", "Poets, dramatists, actors", "Philosophers, statesmen & historians”. Franz Joseph Gall’s rightfully recognised as a great anatomist , pioneering the concepts of localized functions in the brain. He developed the “cranioscopy”, a method to try the personality, mental faculties on the basis of the external shape of the skull. Cranioscopy from cranium : skull and scopos : vision was called later to phrenology from phren : mind and logos : study by his pupil Johann Christoph Spurzheim (1776-1832). In 1791, the first Gall’s publication were two chapters appeared in Philosophisch-medicinische Unlersucliungen-uber Natur u. Kunsi im kranken u. gesunden Zustande des Menschen. In 1810, he published his main work In 1810, he published his Anatomie et physiologie du systeme nerveux en general, et du cerveau en particulier, avec des observations sur la possibilite de reconnaitre plusieurs dispositions intellectuelles et morales de l'homme et des animaux, par la configuration de leur tetes, the first two volumes of which were written with Spurzheim. Image by Wellcome Library n° 11368

As a young boy, James Gillray worked as a letter-engraver but ran away to join a company of strolling player. His first caricature appeared in 1779. From this time until 1811 he engraved nearly 1200 caricatures, a number of which were of medical interest. In his latter years he had many bouts of ill health, and his obsessive anxiety about failing eyesight was reflected in prints and drawings. He was known as a heavy drinker all his life. From 1811, he was subject to fits of madness, and spent his last two years confined to the attic above the print-shop. [Fig. 3]

James Gillray’s true faces

Doublûres of Characters or striking resemblances in Physiognomy. Caricature by James Gillray (1756-1815), published by John Wright (active in 1798) on 1st November, 1798.

This explicit print played on the recent success of Lavater’s Essay. By manipulating the principle that heart and face were essentially connected, Gillray ironically unveiled the ‘true’ faces of the opposition party by pairing their public face with its corrupted countertype. So, for example, we see ‘The Patron of Liberty’ turned into ‘The Arch-Fiend’ or a ‘Character of High Birth’ as ‘Silenus debauching’.

Bust portraits of seven leaders of the Opposition, each with his almost identical double, arranged in two rows, with numbers referring to notes below the title. The first pair are Fox, directed slightly to the left, and Satan, a snake round his neck, his agonized scowl a slight exaggeration of Fox’s expression; behind them are flames. They are ‘I. The Patron of Liberty, Doublûre, the Arch-Fiend’. Next is Sheridan, with bloated face, and staring intently with an expression of sly greed; his double clasps a money-bag: ‘II. A Friend to his Country, Doubr Judas selling his Master’. The Duke of Norfolk, looking to the right, scarcely caricatured, but older than in contemporary prints. His double, older still, crowned with vines, holds a brimming glass to his lips, which drip with wine: ‘III. Character of High Birth, Doubr Silenus debauching’. (Below) Tierney, directed to the right, but looking sideways to the left: ‘IV. A Finish’d Patriot, Doubr The lowest Spirit of Hell.’ Burdett, in profile to the right, with his characteristic shock of forward-falling hair, trace of whisker, and high neck-cloth, has a raffish-looking double with similar but unkempt hair: ‘V. Arbiter Elegantiarum, Doubr Sixteen-string Jack’ [a noted highwayman]. Lord Derby, caricatured, in profil perdu, very like his simian double, who wears a bonnet-rouge terminating in the bell of a fool’s cap: ‘VI. Strong Sense, Doubr A Baboon.’ The Duke of Bedford, not caricatured, and wearing a top-hat, has a double wearing a jockey cap and striped coat: ‘VII. A Pillar of the State, Doubr A Newmarket Jockey’. After the title: ‘“If you would know Mens Hearts, look in their Faces” Lavater.’ 1 November 1798 Hand-coloured etching and stipple Image by Wikipedia

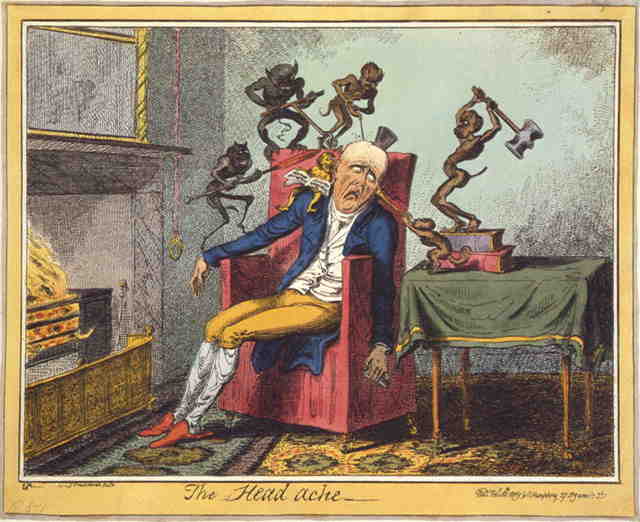

The Cruikshank family is represented by three caricaturists, the Scottish father Isaac and his sons, Isaac Robert and George. The father Isaac was a contemporary of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, and he was part of what has been called “The Golden Age of British Caricature”. He was etcher and engraver, and a first-rate water colour draughtsman. His son Isaac Robert, sometimes known as Robert, was also illustrator and portrait miniaturist. Robert with George collaborated on a series of “London Character”, in 1827. The well known George was considered the “modern Hogarth” during his life [Fig. 4]. When Gillray became insane in 1811, some of his plates were finished by the young George Cruikshank known as illustrators books and caricaturist. George represented the patient as a helpless victim of the medical profession. In later life George had a palsy that influenced the quality of his work.

George Cruikshank’s Head ache

Caricature by George Cruikshank, published by G. Humphrey, 27 St. James's St., London, February 12, 1819.

Another common technique of satirists was to blame physical suffering on sinister beings. Goblins, demons, and imps were drawn as energetic creatures that relished inflicting pain on humans. In the 1819 caricature by George Cruikshank entitled “Head ache,” six demons are the root cause of the main character’s misery. The victim’s excruciating headache, perhaps a migraine, has left him weary and lifeless as he sits in a chair in front of a roaring fire. His head hurts so badly that his eyes have rolled back into his head, revealing only the whites of his eyes. With gleeful enthusiasm the devilish characters are working hard at their gruesome task. A demon swings a large mallet to drive a stake into the man’s skull while another drills a terrifying corkscrew device (an enlarged version of a trephine instrument) into his head. In a previously made hole, another demon pours a liquid substance into his brain. Yet another stands on the man’s arm ready to strike with a spear. Cruikshank amusingly captures how noises can further intensify the trials of a headache sufferer by drawing an imp, sitting on the tortured character’s shoulder, obnoxiously singing into one ear while another imp blows a horn directly into the other ear. Image by Wikipedia

English caricaturists were witnesses of the evolution of Medicine with their discoveries and failures from the standpoint of the patient, medicine as seen by the sick. At the same time they were protagonists of the controversial concept on “brain and character”.

References

- Butterfiled W. The medical caricatures of Thomas Rowlandson. Journal of the American Medical Aassociation 224:113-117; 1973

- Feaver W. Masters of caricature, form Hogarth and Gillray to Scarfe and Levine. Knopf A.A., New York, 1981

- George M. D. Hogarth to Cruikshank: social change and graphic satire. New York, Walker, 1967

- Godfrey R. James Gillray. The Art of Caricature. London, Tate Publishing, 2001

- Haslam F. Views from the gallery. British Medical Journal 311: 1712-3, 1995

- Haslam F. From Hogarth to Rowlandson. Medicine in Art in Eighteenth Century Britain. Liverpool University Press, 1996

- Magee H. R. Doctors in satirical prints and cartoons. Medical Journal of Australia 187: 696-700; 2007

- Patten R. L. George Cruikshank’s: life, times, and Art. New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 1992

- Very Ill. The many faces of Medical caricatures in Nineteenth-Century England & France. University of Virginia. Health System. Claude Moore Health Sciences Library.