Ancient caricature in parody and moral sense by mask and character

God Bes

God Bes came from the Great Lakes of Region of Africa (Twa people a pygm group). Image by Wikipedia

Animals behaving like human beings and related idea of drawing figures which combine human and animal features are among the old representation in the history of caricature, in especially by Egyptians. They were particularly fond of criticizing the foolish behavior of one another and enjoyed representing men as animals and bird. An anthropomorphic characteristic, god had as Bes who is always represented as a dwarf with a large head, popping eyes, protruding tongue and bow legs [Fig. 1]. By grotesque figure he was considered a good luck, maybe in the belief that his hideousness would frighten away evil spirit. This is the tendency to endow human beings with animal forms, or to show animals engaged in human activities to be humorous. This kind-fable is one of the oldest of culture genre, and it is continuous history from Ancient Egypt to the present time. The Greek, and after them Roman, took over not only the idea of humanized animals, but the slightly different one of combining human and animal forms. The grotesque Egyptian god Bes, and embodiment of good luck, is the ancestor of the mischievously anarchic Greek satyr. The difference was that these combinations now tended to be fantastic and satirical, rather than reverent. Greek artists may suggest that certain actions or event can be seen in a comic light. The place for making public statement was the theatre where there is a relationship between theatrical representation of events and people and caricature. Actors used masks characterized by exaggeration or distortion of human face. In tragic and comic mask the Greek, later in Roman period, purpose was the make clear from a distance the precise nature of the character. Mask and costumes were used to exaggerate physical features and to make each character recognizable as comic. The realism was not the main ingredient of classical drama but the masks, mostly elaborated, were often ludicrous, grotesque or awesomely imposing that the actors represent in performance caricatures of the characters they were playing.

Caracalla’s emperor

Statuette de Caracalla (Caracalla's statue) Courtesy of Musée Calvet, Avignon (France), Cliché Fabrice Lepeltier, «L'œil et la mémoire»

Although great myths and stories were worthily illustrated by Greek and Roman artists, they were other parodied such as dwarfs and pygmies, and also Cupid, play a role from the developed classical period onwards. They are shown as soldiers, gladiators, and dancers are engaged in many of the occupations of daily life. In Roman times pygmies became popular as a subject with a representation of power such as the caricature statuette of the Emperor Caracalla. In many Caracalla's portraits his forehead is distorted by sharp wrinkles and his face is rather blunt and flat. He was said to be short of statue and to resemble of a famous gladiator of the time: Tarautus, who was reputedly ugly as violent and bloodthirsty. Caracalla was depicted as a dwarf and it is characteristically Roman because dwarfs were at that time particular figure of amusement and were prized as entertainers and jesters. Caracalla 's mental instability showed in his behavior and his obsession with religion for his identification with an Egyptian God. He was also known for his generosity or kindness and he was represented with distributing cakes as gift in ironic sense [Fig. 2]. These parodies and moral features were the aim of caricature in the following period of the Middle Age because caricature, and indeed all satire, is only really effective when it makes reference to moral norm. For this reason the medieval Dance of Death probably marks the true beginning of caricature. The Dance of Death was not merely gruesome and apocalyptic, it also contained a strong elements of social criticism and sardonic humour. In all its versions, it pointed the same moral: Death as universal leveler in a rigidly hierarchical society. This is a satyr allegory about Medicine that can't change the destiny of the suffering humanity.

Venetian hemispasm

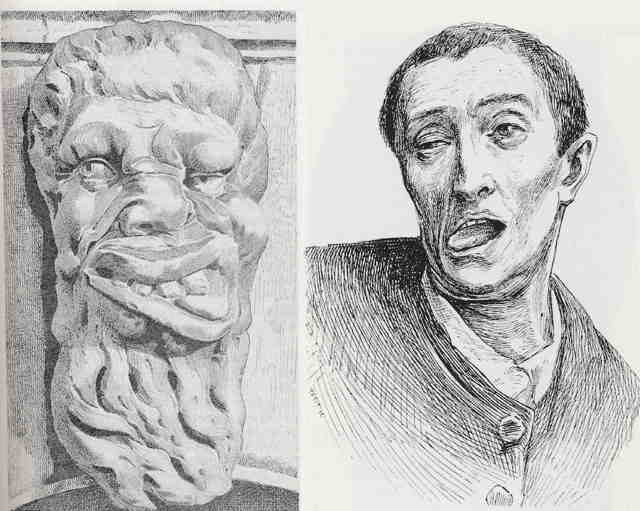

Mascherone (Big Mask) of the Santa Maria-Formosa in Venice and hemispasm glosso-labial sign reported by Charcot in 1888 in ‘Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière’ (Private collection).

A destiny can be monstrous during the life as depicted by a grotesque mask, an example is that called “Mascherone” (Big Mask) of the Santa Maria-Formosa in Venice with a big head, inhuman and monstrosity, sneer, with an expression that reveals a deformation of difficult interpretation. The protrusion of the tongue was popular and considered in the Middle Age as a mockery. Charcot interpreted it as a hemispasm glosso-labial sign of a possible hysterical origin in an age considered plenty of fantasy. The French neurologist concluded that the grotesque Venetian mask is a Neuro-pathological deformation that the medieval artist depicts with humour. Charcot demonstrated that behaviour of his patients seen at the Salpêtrière could be similar to those found in medieval and other mannerist painting [Fig. 3].

References

- Charcot J-M, Richier P . Le mascheron grotesque de l'église Santa Maria Formosa, a Venise et l'hémispasme glosso-labié hystérique. Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpêtrière 1: 87-92;1888

- Charcot J-M, Richier P. Difformes et Malades dans l'Art . Paris, Lecrosnier et Babé Libraires-Éditeur, 1889

- Lucie-Smith E. The art of caricature. London, Orbis Publishing Limited, 1981

- Robinson D M. Caricature in Ancient Art. The Bulletin of the College Art Association of America, 1: 65-68; 1917

- Weber A. Tableau de la caricature médicale depuis les origines jusq'à nos jours. Paris, Édition Hippocrates, 1936